Last Updated on April 15, 2024 by Ryan

- Types of sinkholes

- Sinkholes in Florida

- How Deep Are Sinkholes in Florida

- How to predict Sinkholes?

- Sinkholes In Florida

- What are Florida Sinkholes?

- Why is it that Florida has so many sinkholes?

- What is the different type of Florida sinkholes?

- What are the reasons which bring Florida sinkholes?

- What are the signs of Florida sinkholes?

- Major Sinkhole Warning Signs

- What should one do when a sudden sinkhole arises in Florida?

- Facts about Sinkholes in Florida

- Where are the sinkhole areas in Florida?

- Where Are The Most Sinkhole Incidents in Florida?

- Sinkhole Alley

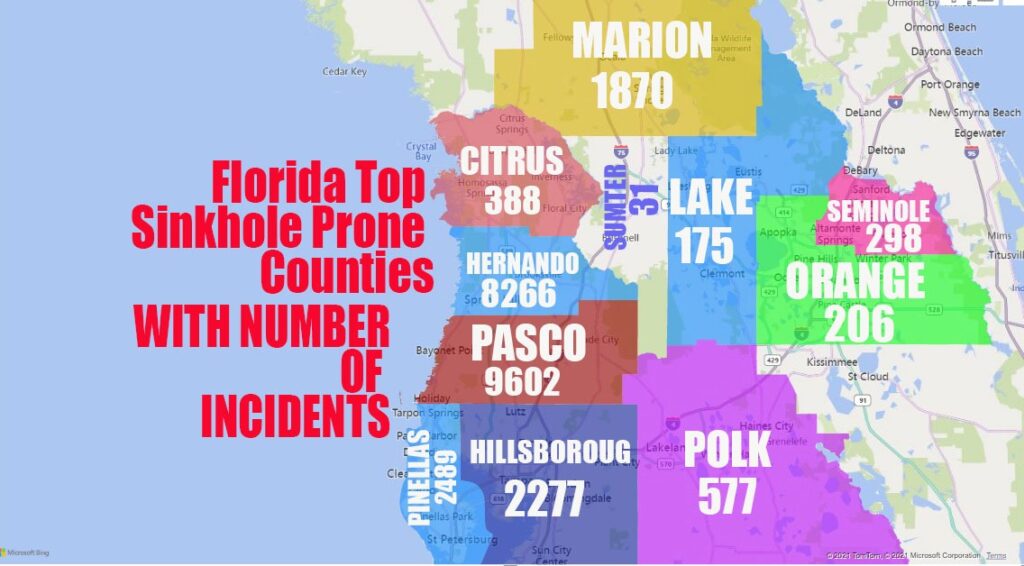

- Top 10 Florida Sinkholes Prone Counties

- Real Sinkholes

- Risk of Sinkholes

- Wrapping up message

- Conclusion

Types of sinkholes

Since Florida is prone to sinkholes, it is a good place to use to discuss some different types of sinkholes and the geologic and hydrologic processes that form them. The processes of dissolution, where surface rock that are soluble to weak acids, are dissolved, and suffusion, where cavities form below the land surface, are responsible for virtually all sinkholes in Florida.

DISSOLUTION SINKHOLES

Dissolution of the limestone or dolomite is most intensive where the water first contacts the rock surface. Aggressive dissolution also occurs where flow is focused in preexisting openings in the rock, such as along joints, fractures, and bedding planes, and in the zone of water-table fluctuation where groundwater is in contact with the atmosphere.

Rainfall and surface water percolate through joints in the limestone. Dissolved carbonate rock is carried away from the surface and a small depression gradually forms. On exposed carbonate surfaces, a depression may focus surface drainage, accelerating the dissolution process.

Debris carried into the developing sinkhole may plug the outflow, ponding water and creating wetlands. Gently rolling hills and shallow depressions caused by solution sinkholes are common topographic features throughout much of Florida.

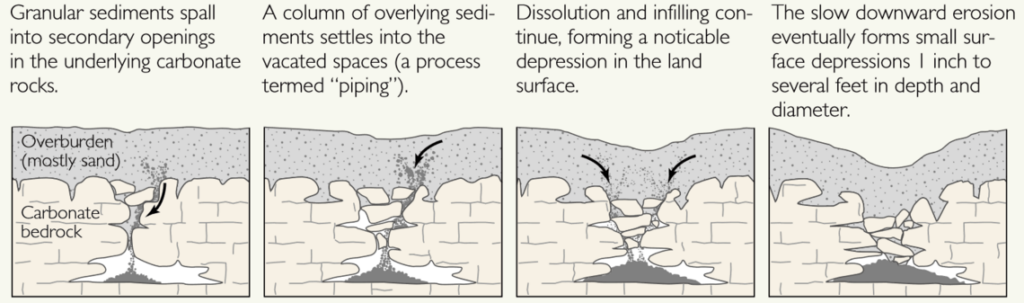

COVER-SUBSIDENCE SINKHOLES

Cover-subsidence sinkholes tend to develop gradually where the covering sediments are permeable and contain sand. In areas where cover material is thicker, or sediments contain more clay, cover-subsidence sinkholes are relatively uncommon, are smaller, and may go undetected for long periods.

- Granular sediments spall into secondary openings in the underlying carbonate rocks.

- A column of overlying sediments settles into the vacated spaces (a process termed “piping”).

- Dissolution and infilling continue, forming a noticeable depression in the land surface.

- The slow downward erosion eventually forms small surface depressions 1 inch to several feet in depth and diameter.

In areas where cover material is thicker, or sediments contain more clay, cover-subsidence sinkholes are relatively uncommon, are smaller, and may go undetected for long periods.

COVER-COLLAPSE SINKHOLES

Cover-collapse sinkholes may develop abruptly (over a period of hours) and cause catastrophic damages. They occur where the covering sediments contain a significant amount of clay. Over time, surface drainage, erosion, and deposition of sinkhole into a shallower bowl-shaped depression. Over time, surface drainage, erosion, and deposition of sediment transform the steep-walled sinkhole into a shallower bowl-shaped depression.

- Sediments spall into a cavity

- As spalling continues, the cohesive covering sediments form a structural arch.

- The cavity migrates upward by progressive roof collapse.

- The cavity eventually breaches the ground surface, creating sudden and dramatic sinkholes.

Sinkholes can be human-induced

New sinkholes have been correlated to land-use practices, especially from groundwater pumping and from construction and development practices. Sinkholes can also form when natural water-drainage patterns are changed and new water-diversion systems are developed.

Some sinkholes form when the land surface is changed, such as when industrial and runoff-storage ponds are created. The substantial weight of the new material can trigger an underground collapse of supporting material, thus causing a sinkhole.

The overburden sediments that cover buried cavities in the aquifer systems are delicately balanced by groundwater fluid pressure. The water below ground is actually helping to keep the surface soil in place. Groundwater pumping for urban water supply and for irrigation can produce new sinkholes in sinkhole-prone areas. If pumping results in a lowering of groundwater levels, then underground structural failure, and thus, sinkholes, can occur.

Sinkholes in Florida

Sinkholes are usually just a pain in the neck for property owners, but when tragedy strikes, it’s the stuff of nightmares. Jeffrey Bush, who was asleep in his bedroom when a sinkhole pulled him 20 feet down, is one of Florida’s six known sinkhole deaths. His remains were never found.

In recent years, the frequency of recorded sinkholes in The Villages has increased. Residents reported “many” sinkholes in 2016, but none harming homes, according to an official with The Villages Public Safety Department, according to the Orlando Sentinel. The same is true for 2015; three sinkholes impacted six properties in 2014.

That independent news source, on the other hand, recorded at least 32 sinkholes in 2017. At least eight residences were damaged, as well as a country club, a busy junction, a Lowe’s home improvement shop, and the world’s largest American Legion post.

(The Villages’ developer’s newspaper, The Daily Sun, commented on none of them save the one near the major junction, saying merely that it was “later found not probable” to be a sinkhole.) Villages-News reported at least 11 sinkholes in the first three months of 2018, damaging eight homes—all before sinkhole season began in early April. This week, four additional sinkholes appeared.

Florida Sinkholes Causes

A sinkhole on Shoal Drive in Hudson that buried the backside of a house in 2012. Pasco County Fire officials claimed the sinkhole was 40 feet wide and 20 feet deep at the time the photo was taken. Read more…

Florida Sinkhole Season

The fact that there is a “sinkhole season,” just as there is a “tornado season” and a “hurricane season,” demonstrates the complexity of the danger. The fact that Florida is constructed on a carbonate base, mostly limestone, underpins all of them. Rainwater, which turns acidic as it seeps through the soil, dissolves that rock very readily.

The resultant landscape is honeycombed with cavities, known as “karst.” When a hollow gets too large to maintain its roof, the clay, and sand above it collapses, leaving a gaping hole at the surface.

Primary Cause of Sinkholes in Florida

Water—either too much or too little—is the primary cause of sinkholes. Florida’s typically wet soil has a karst-stabilizing impact. During a drought, however, cavities that were previously supported by groundwater dry out, making them unstable. The weight of pooled water can strain the soil after a severe downpour, and the quick rush of groundwater can wipe out voids.

At the start of 2017, Central Florida was experiencing a severe drought, which was followed by Hurricane Irma’s torrential rains, which reached The Villages in September—and a deluge following a drought is the ideal setting for a sinkhole epidemic.

However, Mother Nature’s significant events in 2017 do not explain for the current epidemic of sinkholes. Sumter County’s weather has been very average. So, what exactly is going on here?

Mand-Made Growth

The greatest consistent reason for rising sinkholes, it turns out, is man-made growth. The weight of new structures bears down on weak places; underground infrastructure can lead to leaking pipes; and, perhaps most importantly, groundwater pumping disturbs the delicate water table that keeps the karst stable.

And The Villages has been on a construction frenzy. It was the United States’ fastest expanding metropolitan region. It’s been in the top ten for four years in a row (2013-16), and it’s still there.

Journalist Andrew Blechman predicted in his 2008 book Leisureville that The Villages will “end its build-out—an industry phrase for the point at which a project is complete—in the very near future,” with a population of “110,000 inhabitants.” However, a decade later, the population had surpassed 125,000 people.

The Villages announced a 93 percent increase in house development last year, as well as a new property purchase that would generate up to 20,000 units. Another property transaction for 8,000 additional houses is about to be finalized.

Golf Courses

More golf courses will be built as a result of the additional houses, which will increase the total number of golf courses in The Villages to 49 (the second most per capita in the United States). Retention ponds created on those courses have the potential to seep into the karst, causing sinkholes. Irrigating The Villages’ 49 golf courses and tens of thousands of lawns is also a big danger concern.

Veteran writer Craig Pittman recalls in his 2016 book Oh, Florida how a buddy who worked at the Daily Sun told him that the staff was never to publish two things: 2) “The countless sinkholes that open up due of all the water being drained from the aquifer to keep lawns and golf courses green.”

Lauren Ritchie of the Orlando Sentinel writes in a critical piece that the nascent neighborhood had a water permit to consume 65 million gallons per year in 1991, but by 2017 that rate had risen to “a staggering 12.4 billion gallons per year.”

A contentious plan by a bottling firm to pump almost half a million gallons of water per day—and quadruple that pace during peak months—is also threatening the local aquifer in Sumter County. Pumping will begin shortly, despite Villagers’ objections that a lowering water table could cause sinkholes.

How Deep Are Sinkholes in Florida

The biggest sinkhole in recent memory occurred in Land O Lakes, Florida, and measured almost 260 feet across.

This monster sinkhole caused seven homes to be condemned and required more than 135 truckloads of limestone to fill. More recently, a sinkhole about 20 feet across and 35 feet deep has been threatening residents of The Villages, a popular retirement community.

The Land O Lakes sinkhole was uncommonly large. Scientists believe that the average sinkhole in Florida is about 11.2 feet across. However, the depth of sinkholes varies widely: some are just a few feet in depth, but others can be startlingly deep. An infamous sinkhole in 2013 in Tampa was more than 20 feet deep and swallowed a man’s house with him in it – the man, unfortunately, perished.

How to predict Sinkholes?

1- Ground penetrating radar (GPR)

The unpredictability of sinkholes is at the heart of that anxiety element. They generally appear out of nowhere, and detecting weak places in the earth is difficult. “Drilling exploratory holes in The Villages is difficult because rock can be 5 feet down in certain areas and 100 feet down if you go 20 feet to the side,” Wilshaw explains.

Wilshaw, who owns a firm that specializes in analyzing sinkhole danger, is frequently recruited to examine properties using ground penetrating radar (GPR), the most effective method of detecting holes. However, because Florida law does not mandate it, he claims that many homebuilders “will do absolutely nothing and instead rely on the end user” to check for cavities. He describes it as “a little bit of the Wild West.

2- NASA’s technology

Is there any other technology that can assist anticipate sinkholes than GPR? NASA’s technology has demonstrated its worth: When an interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) sensor is flown repeatedly over a region prone to sinkholes, especially the slow-forming ones known as “cover-subsidence,” it detects minute changes in ground elevation over time.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) reached out to NASA for assistance after that usage of InSAR became public in 2014, but when I checked in with a DEP representative, she stated it wasn’t going to happen anytime soon.

Sinkholes In Florida

The fact that Florida has many sinkholes comes as no surprise to most of us. Sinkhole areas in Florida are well-known in the United States. Sinkholes in Florida make national headlines year after year as the geologic phenomenon seems to swallow more of the Sunshine State (Brown, 2019).

What are Florida Sinkholes?

Florida sinkhole is a depression in the earth that may result from a rock dissolved in the water beneath. It sometimes may get too long and deep that it can engulf a large house at one. In Florida, a sinkhole is a common thing and the most threatening one. Dissolution of the rock, usually the limestone, is more prevalent in areas where the precipitation rate is high.

Limestone is such a rock that the movement of water quickly erodes it. On the other hand, Florida has a thick bed of limestone, which is the primary cause of the increasing sinkhole rate in Florida.

Sinkholes in Florida are most common in karst terrain areas. Karst terrain areas are those areas where the water bed beneath the earth dissolves the water-soluble rocks like limestone, dolomite, etc., resulting in a large crack on the rock bed which is prolonged to several areas and lands. In short, karst terrain is the areas having a break in their rock bed.

In the United States, 20% of the land is Karst land, and the most famous point of the world regarding the karst land is also present in the United States named Kentucky. People usually take it for granted, but people should take care of the sinkhole as it may become a global issue once a day.

It is not just a problem for Florida, but sinkholes are also significant in many other countries nowadays. It is just that sinkhole rates in Florida are high as compared to other states and countries.

In the United States, 20% of the land is Karst land, and the most famous point of the world regarding the karst land is also present in the United States named Kentucky.

People usually take it for granted, but people should take care of the sinkhole as it may become a global issue once a day. It is not just a problem for Florida, but sinkholes are also significant in many other countries nowadays. It is just that sinkhole rates in Florida are high as compared to other states and countries.

Government should devise an effective policy to manage this sinkhole in Florida to keep themselves safe from future threats. One can estimate the danger associated with the sinkhole through one incident of the past.

In 2014, in the National Corvette Museum in Bowling, a sinkhole opened under the floor, and it engulfed eight significant corvettes, display stands, and rails. This gives an outlook of the threat and happening associated with the sinkhole.

Sinkholes in Florida are now a leading common problem. It comes basically in three types as listed below:

Why is it that Florida has so many sinkholes?

Sinkholes can grow anywhere in Florida, but the karst limestone environment in west-central Florida causes the most activity. Long-term weather patterns, heavy acidic rains, and drought-like conditions are all factors that increase the risk of sinkhole activity (Grape, n.d.).

The regional map on the right shows sinkhole locations identified by the Florida Geological Survey since 1954. Although it does not represent all sinkhole occurrences in Florida, it does lead to an understanding of the problem’s scale (Bodenner, 2018).

What is a Limestone Rock?

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed principally of calcium carbonate (calcite) or the double carbonate of calcium and magnesium (dolomite). It is commonly composed of tiny fossils, shell fragments and other fossilized debris.

What is the different type of Florida sinkholes?

Cover Collapse Sinkholes:

Solution Sinkholes:

Subsidence Sinkholes:

Cover Collapse Sinkholes

Cover collapse sinkholes occur in those areas where a cavity is present in the limestone bed. As it is permeable, it continues to enlarge until there surface cover can no more support its weight.

Solution Sinkholes

It is a prevalent type of Florida sinkhole. It occurs when there is a thin bed of permeable land and covered by limestone bedrock. Solution sinkholes bring the exposure of land or soil. It is pretty hard to handle, but the repairing can be done on a technical level.

Subsidence Sinkholes

In subsidence sinkholes, the sand particle moves downward and replaces the other sand particles until they reach the limestone bed and replace it altogether. Subsidence sinkholes are permeable sinkholes too and non-cohesive.

One should be careful about them as they are most challenging to handle even compared to solution sinkholes in Florida. Florida Sinkholes are very famous, such as the Diesetta sinkhole in Texas. It is a monster sinkhole as it is approximately 900 feet wide and 400 feet deep.

Except that there are many other Florida sinkholes too, like winter park sinkhole in Florida, Devil’s sinkhole in the Edwards country or place, Safferna, which is also present in Florida, etc. Winter park sinkhole is also a giant sinkhole in Florida, and it accounts for 350 wide and 750 deep. As compared to them, the Seffner sinkholes in Florida are pretty small in size.

They are 20 feet wide and 50 feet deep. What about sinkholes in Edward’s country? They are also small in size and account for 40 feet across and 60 feet deep. Sometimes Florida sinkholes may become more profound and comprehensive if we leave them untreated initially. So, we should not leave them untreated, but we should try to repair and recover them as we see and as soon as possible.

What are the reasons which bring Florida sinkholes?

Florida has more sinkholes than any other state in the USA. It is just a typical day out, a thing that occurs in Florida. The primary cause of the Florida sinkhole is the heavy rain than any other thing. As the heavy rain and on the other hand, if it is acidic to bring sinkhole in Florida more rapidly.

Heavy rain means there is plenty of water to dissolve the rock bed, and on the other hand, if it is acidic too, it speeds up the formation of Florida sinkhole. Florida sinkhole is merged up in the dry seasonal changes and brings a vast sinkhole that is wider and deeper than the single sinkhole.

The occurrence of sinkholes is highly dependent on the land’s geological properties. Its thickness of rock bed, available rock type, seasonal changes, etc. They vary from area to area, state to state, and county to country.If the sinkhole occurs in an area that is less populated or not populated by men, are con considered, and the respective authorities do nothing.

But if it appears in a populated place, it becomes a matter of concern. But it is barbaric because these neglected sinkholes may merge and bring deeper and wider sinkholes, which can get more difficulties in the future. So, people or respective authorities should not ignore them.

What are the signs of Florida sinkholes?

Signs are a fundamental thing. It will give us a prediction of the possible happening of the future. One should know the signs of sinkholes in Florida as he is a simple homeowner, caretaker, or successful.

If we know the signs of sinkholes, we can recognize that it is either a sinkhole or a simple hole and can do some steps to recover and prevent the sinkholes in the future. Florida sinkholes have many signs, but some vital signs are listed below:

- Sudden cracks at the junction of the house, building, and the area. It may occur due to harsh natural environmental changes like the weather, acid rain, thunderstorm, etc.

- Crack in exterior blocks or buildings and colonies. It may occur due to poor land management while making the houses or designing the settlements.

- Street depression is also the initial but significant sign of a florid sinkhole. It occurs due to improper land balancing while making the roads and streets. The soil is not properly settled.

- Separation and cracks in concrete. It may occur due to the use of lousy quality concrete and occurs when a small amount of concrete is used compared to what was required.

- Ceiling Cracks.

- Poor water management. Or loss of the water pool.

- Cracks in the foundation or building.

- Sinkhole in Florida may also result in the welting of the plants.

- Florida sinkhole may also result when your neighbor is also affected by a sinkhole or have a sinkhole.

- The sloping of the floor is a ubiquitous sign of a sinkhole in Florida.

- Basic cavity foundation.

It will be easy for you to deal with the Florida sinkhole when you know the sign of a sinkhole. Before making a house, you should always focus on the primary elements, which may not form a sinkhole in the future.

It would be best if you always looked for the proper balancing of soil bed and water management first, then the quality of concrete is the other most vital thing to consider. On the other hand, you are likely to have sinkholes in Florida when you observe such signs.

Major Sinkhole Warning Signs

- Cracks in joint interior areas

- Exterior paneling or block cracks

- Squeaky windows and doors / Cracked doors and windows / Windows and doors become harder to close

- Yard or street downturns

- Separations, cracks, and gaps in concrete

- Wilting plants

- Neighbors with sinkholes

- Actual cavity-forming

- Foundation cracks

- Ceiling cracks

- Cracked walls

- Settling foundation

- Sloping floors

- Loss of pool water

- Spongy spots start appearing in the yards or on the surface of the earth.

- Trees and plants become tilted

- Cracked surface of the earth

- Sinking yard

- Driveway become uneven

- Leaning structures

Keep a strict eye on your home and nearby infrastructures. If you saw any sign at your house or around your house, call the emergency helpline and inform them about the situation before getting worse. If any sinkholes activity happens near you, stay calm and don’t panic, all you need to do is leave the area as soon as possible when you see any activity sign.

Safety measures

- If you’re are standing in a public area, never go near the sinkhole

- if you are in a residential area, try to leave your houses and buildings as soon as possible. Your priority should be calling emergency helplines.

- Inform your insurance company.

- Inform people around you to leave the area.

- Tape the area so that no one can walk near that area.

- Call a professional to inspect the activity.

Predicting sinkholes is almost impossible, and most probably, sinkholes prevention is not possible. All we can do is when any sign starts appearing, we should inform professional and emergency helplines to inspect the situation. If the sign is pointing to sinkholes formation, we can take safety measures before time.

Don’t take any risk in your life and the people around you. Human life is the priority for any state. Florida is making many and continuous safety arrangements for the people to protect them from any significant damages and prevent the state from any major economic damage.

Sinkholes affecting building / Land

Sinkholes of Florida affecting building and local property at a great scale. Not only large buildings but houses are also not safe from the effects of sinkholes. Sinkholes affect the land before the formation and after formation. Before the start of any activity, doors and windows of houses and buildings start getting affected. When sinkholes occur, they leave empty holes on earth that are useless.

What should one do when a sudden sinkhole arises in Florida?

They are not sudden, but if the sinkhole occurs suddenly, you should call to the concerned sinkhole helpline in Florida and then keep the people away from it because, in some areas like karst areas, there is a chance that a sinkhole may occur suddenly and be a larger and deeper one.

So, you should keep the lives away. On the other hand, if there is a small sinkhole in the garden or on any area of the house and other foundation, you should account for it on the number one to repair it. Moreover, you should do your best to recover and repair this sinkhole as much as possible and as soon as possible.

Because if it is prolonged, it may bring you to severe, life-threatening problems. According to FDA, in the United States, the sinkhole problems exist no more, but it is still present in its Florida state, where a common issue still needs a well-designed and well-organized policy.

Facts about Sinkholes in Florida

- The depression in the pipes may form a sinkhole. Depression is not a sinkhole in itself, but it can lead you towards having a sinkhole in Florida as depression dissolves the layer of soils and land and can lead you towards having a sinkhole in the future.

- A sinkhole in FL is nearly impossible to predict. It is true to somehow but as much. You can estimate the occurrence of a sinkhole in an area by using the canopy signifying method, also abbreviated as CPT. Moreover, by the sinkhole sign in Florida, a rough estimation can be formulated because of a sinkhole in Florida.

- Spring and other water bodies can lead to a sinkhole. It is a fact because these water bodies land a hand in dissolving the upper layer of land and can form a sinkhole in Florida or every area of land.

- If we talk about Lake Eola, it is also is a result of a sinkhole. It is 23 feet and 8 inches deep. Lake Eola is 100 feet away from the east fountain, which shows that the lake Eola may result from the east rush etc.

It is because we left the sinkhole as it is in its early stage. A sinkhole in its early stage can be recovered as a hole in a tooth is refiled, the same as an island is formed on a sinkhole by filling and repairing a sinkhole. Still, it can only be done and successful when you do it at the initial stage of a sinkhole.

Later on, it became more comprehensive and deeps which were challenging to handle and repair. There is also nothing wrong if I say that it is almost impossible to repair.

Sinkhole Research

“The major problem here is that the state doesn’t really support much sinkhole research,” Brinkmann says, “especially since real estate remains one of the state’s primary economic engines.”

“With the exception of this tiny study, the federal government has not actually financed any substantial studies on the issue. Every year, millions of dollars are spent on tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes, and hurricanes, yet little, if any, is spent on sinkhole research. [The former] are indeed heinous, but they are one-time theatrical happenings. Sinkholes are a continual hazard, and the majority of the harm occurs over time. The annual property loss caused by sinkholes is staggering”—a conservative estimate of $300 million is used.

As climate change worsens, the impact might become far worse. “As sea levels rise as a result of climate change, groundwater levels in near-coastal locations will rise as well, resulting in more sinkhole flooding,” Veni forecasts. “Studies on the possible degree of such flooding and its ability to induce fresh sinkhole collapses are just getting started,” he says, adding that he’s working on one with a colleague in Florida.

Some Villagers are on the verge of giving up. “We thought we’d be here for the rest of our days when we moved [to the Village of Glenbrook] in 2012,” a member of the “Talk of the Villages” web forum wrote on March 5 after a sinkhole forced his neighbors to evacuate, but “now we’re considering moving again, which is the last thing I wanted to do.”

(A dozen sinkholes developed in an Ocala community not far from Glenbrook, garnering national headlines, less than two months later, forcing another eight family to from their homes.) “I am dreading when the rainy season comes,” another Villager said ominously, referring to the commencement of the rainy season, which is expected to begin on May 27 in the region.

However, the rainy season arrived early this year: on May 20, four sinkholes erupted in Calumet Grove, the Village that had been hit by seven sinkholes in February. Due to a subtropical storm system developing off the coast, thunderstorms are anticipated to persist.

Frank Neumann, an 80-year-old resident who was evicted from his house in February, talked with Villages-News. According to the website, “Prior to Monday’s sinkhole activity, Neumann said he hoped to have his house restored and continue in the area he’s lived in for 14 years—largely because of the friendships he and his wife had established there.”

“However, as he stood in his front yard, gazing at the second wave of damage to hit his home in 95 days, he said he wasn’t so sure staying in The Villages was a smart choice.”

Florida Division of Emergency Management (DEM)

Sumter County is conspicuously absent from RiskMeter’s top ten list. However, that 2011 list was based on sinkhole insurance claims, and a large number of them were erroneously filed in the years leading up to 2011, when Florida lawmakers reformed the misused system.

The 2013 Hazard Mitigation Plan, prepared by the Florida Division of Emergency Management (DEM), gave Sumter a “medium” risk for sinkholes, which came two years later (just as The Villages was commencing its four-year development run). Only eight other counties were rated as being at a higher risk.

However, as DEM admitted, the 2013 assessment was “imperfect and inadequately justified by existing geologic data” since it was based largely on public reports of sinkholes that had not been validated by geologists.

Clint Kromhout of the Florida Geological Survey won more than $1 million in government money in 2013 to travel throughout Florida verifying sinkholes and creating a prediction map indicating which regions are most “relatively vulnerable.”

“The goal for the scale of the state map is at least the county level,” Kromhout said, “but Kromhout said he hopes they will be able to get to a neighborhood-by-neighborhood detail,” according to James L. Rosica of the Tampa Bay Times, who was one of the many reporters Kromhout spoke with during the three-year study.”

Homeowners Insurance

Given the fragile nature of karst, a sinkhole can occur even after a location has been studied and certified secure from sinkholes. Wilshaw advises, “It’s better to just cross your fingers and get insurance.” However, homeowners insurance only covers “catastrophic earth collapse,” which occurs when a sinkhole renders a property inhabitable.

Any damage that falls short of that must be covered by sinkhole insurance, which in Florida generally has a deductible of 10% of the home’s value.

Even after a sinkhole has been fixed (or “remediated,” as the technical phrase goes), it might resurface. The Villages’ most spectacular sinkhole, near Buttonwood (just look at this shot), burst out many months after repair began. The sinkhole that killed Jeffrey Bush did the same.

Where are the sinkhole areas in Florida?

Where Are The Most Sinkhole Incidents in Florida?

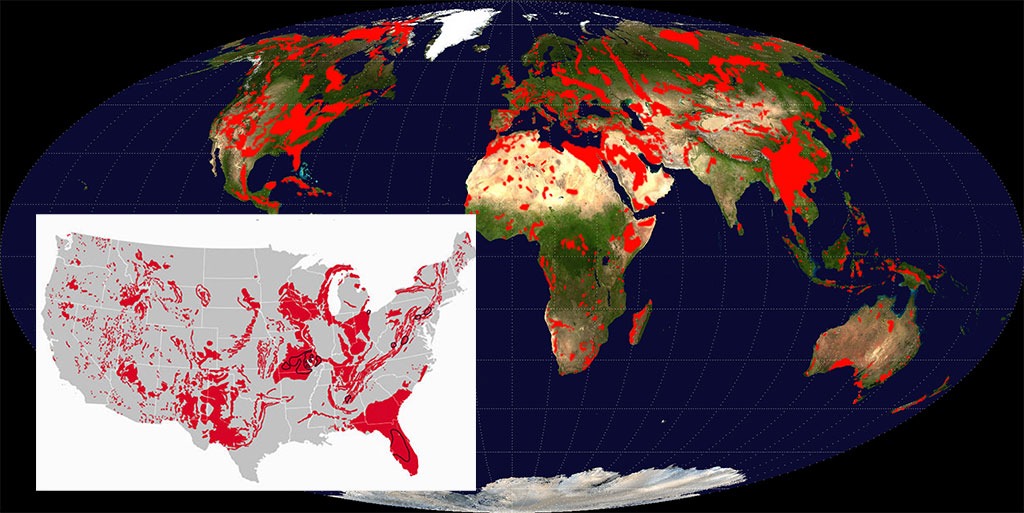

First lets take a look at World sinkhole map Vs the USA sinkhole map:

Here you can find interactive sinkhole maps of Florida. Also sinkhole maps of the USA and the world Sinkhole map.

Florida Sinkhole Areas

Sinkholes are common where the rock below the land surface is limestone, carbonate rock, salt beds, or rocks that can naturally be dissolved by groundwater circulating through them. As the rock dissolves, spaces and caverns develop underground. Sinkholes are dramatic because the land usually stays intact for a while until the underground spaces just get too big.

If there is not enough support for the land above the spaces, then a sudden collapse of the land surface can occur. These collapses can be small, or, as this picture shows, or they can be huge and can occur where a house or road is on top.

The most damage from sinkholes tends to occur in Florida, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania.

Areas prone to collapse sinkholes

The map below shows areas of the United States where certain rock types that are susceptible to dissolution in water occur. In these areas the formation of underground cavities can form, and catastrophic sinkholes can happen.

These rock types are evaporites (salt, gypsum, and anhydrite) and carbonates (limestone and dolomite). Evaporite rocks underlie about 35 to 40 percent of the United States, though in many areas they are buried at great depths.

Where Are The Most Sinkhole Incidents in Florida?

5 Major Florida Sinkholes Areas

Sinkhole in Florida is a common and most prevailing issue nowadays. Ecologists are busy finding the best solution for them. Let’s have a big eye on major Florida sinkholes.

- Yellow Zone

- Green Zone

- Blue Zone

- Pink zone

- White Zone

Florida sinkholes are divided into four zones, ranging from yellow to pink. Categorizing zones helps to read a Florida map and quickly identify the sinkhole problem in a particular area. Let’s have a look at them one by one:

Yellow Zone

This zone includes Hialeah, Miami, Hollywood, and Coral Springs. The presence of shallow Florida sinkholes characterizes these cities or this zone. Moreover, these cities have a thin bed of carbonates rock. That’s why Florida sinkholes are common in these cities.

Green Zone

The Green zone includes port st. Lucie, Fort Lauderdale Orlando cities. In this zone, there is porous sand and which leads to sinkholes in the respective areas. Cover collapse and subsidence holes are widespread, then the solution sinkholes in this zone. They have a range from 20 to 200 feet. We should take care of such Florida sinkholes as they enlarge quickly and can bring horrible results.

Blue Zone

The cities in this zone include St. Petersburg, Tampa, and Tallahassee. This zone is characterized by cohesive but permeable land or soil, resulting in sudden collapse sinkholes in Florida.

Pink zone

This area includes two cities, named Jacksonville and St. Augustin. This zone has a shallow embedded bed of carbonate rock that is not only embedded but also interconnected. Due to this shallow bed of carbonate rocks, there are very rare Florida sinkholes. Cover sinkholes, but small in size Florida sinkholes, may occur in this area.

Sinkholes are the natural part of our ecosystem, but our daily activities are also a leading factor in Florida’s sinkhole problem. In a few areas, if we can’t control the formation of sinkholes, it is ok. But it is not ok if we leave them untreated. We should repair them as quickly as we can without any regret.

White zone

Orlando is one of the state’s safer zone when it comes to avoiding catastrophic sinkholes.

Sinkhole Alley

Kromhout’s 2017 paper, according to Veni, the karst expert I spoke with, is “the most extensive, comprehensive examination of sinkhole risk that I’m aware of.” (Kromhout, as well as a spokesperson for The Villages, declined to be interviewed for this article.) The 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan, which was released in February, featured its long-awaited prediction map.

That’s the extent of the map’s detail. “Most significantly, the favorability map is not of sufficient detail to offer site specific information on sinkhole development,” according to the Sinkhole Report. The Villages are mostly in Sumter County’s northern half, which is virtually entirely in the red zone.

Is the Sinkhole Report really that useful? “It isn’t the prediction model that some hoped for (it would be quite difficult to construct one), but it does improve the science,” says Robert Brinkmann, a geology professor at Hofstra University who co-authored Florida Sinkholes: Science and Policy and owns a home in Sinkhole Alley.

Where is Florida Sinkhole Alley?

Where is Florida sinkhole alley? West-central areas of Florida like “Pasco, Hernando, Hillsborough” has many sinkholes. The insurance between 2006 and 2010 claims Two-third part of Florida. In the past, the formation of sinkholes was not that frequent as it is nowadays. For the past few years, it has been seen in Florida that sinkholes are occurring more frequently than ever. Sinkholes are one of the significant issues that governments and people of Florida over many years. It is damaging Florida’s economy. To prevent the state from significant demands, scientists have started a new project to predict sinkholes’ formation.

Central area is the attraction for Florida people so huge amount of people starts moving to central counties of Florida, they become more populated than ever. The main reason behind frequent sinkholes formation is the soluble limestone that is present underground. That limestone when start dissolving with underground acidic water and rainwater, they form underground cavers and cracks. Significant issues arise because of farming activities. People built pipelines without proper backfilling, and when farmers pump the water from this point, the real action behind sinkholes starts.

Sinkhole Alley Map

See All Florida Counties Sinkhole Maps Here

Famous sinkholes of Florida alley

- Dover 2010

- Florida high school 1962

- Dunedin 2013

- Winter park 1981

- Locals 1950

- Alligator Road, Franklin county 2005

- Frostproof 1991

Top 10 Florida Sinkholes Prone Counties

Florida sinkholes area referring to which part of Florida?

Sinkholes are quite frequent in Florida, making it difficult for people to choose a property that is secure from them.

On the Florida sinkholes Department of Environmental Protection’s (FDEP) website, there is a map kept by the Florida Sinkholes Geological Survey that shows where sinkholes have been recorded.

The data, however, only chronicles “subsidence” occurrences that have been recorded by observers, according to the agency.

The Florida Sinkholes Geological Survey maintains a map that indicates where “subsidence” occurrences have been documented in the state.

“Reported occurrences tend to cluster in populous locations where they are easily observed and often impact roads and houses,” according to the FDEP’s website‘s sinkhole FAQ section.

- Pasco County, FL

- Hernando County, FL

- Pinellas County, FL

- Hillsborough County, FL

- Marion County, FL

- Polk County, FL

- Citrus County, FL

- Seminole County, FL

- Orange County, FL

- Suwannee County, FL

- Lake County, FL

On the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s (FDEP) website, there is a map kept by the Florida Geological Survey that shows where sinkholes have been recorded.

The data, however, only chronicles “subsidence” occurrences that have been recorded by observers, according to the agency.

The Florida Geological Survey maintains a map that indicates where “subsidence” occurrences have been documented in the state.

“Reported occurrences tend to cluster in populous locations where they are easily observed and often impact roads and houses,” according to the FDEP’s website‘s sinkhole FAQ section.

“While the data may contain some real sinkholes,” the website adds, “the majority have not been confirmed by specialists and are collectively referred to as subsidence occurrences.”

Sinkholes are prevalent when the geology under the land surface contains limestone, carbonate rock, salt beds, or rocks that may be naturally dissolved by groundwater passing through them, according to the USGS.

According to the USGS, sinkholes cause the most damage in Florida, as well as other Southern states such as Texas, Alabama, Missouri, and Kentucky.

According to the FDEP, much of Florida is underlain with limestone, no portion of the state is totally free of the risk of sinkholes, however there are some areas that are particularly vulnerable.

Sinkholes are particularly frequent in Pasco, Hernando, and Hillsborough counties in Florida, which are collectively known as “Sinkhole Alley.”

The Villages Sinkhole

The Villages is characterized as “Disney for Seniors” for a variety of reasons.

The Villages, the world’s biggest retirement community, is also one of America’s safest and most relaxing places to live. Sumter County, which is nearly completely made up of Villagers, ranks 62nd out of 67 counties in Florida for violent crime, owing to the county’s median age of 66.6, the highest in the country.

The presence of gates, guard booths, and required visitor identification cards contributes to the low crime rate. The number of vehicular deaths is quite low, which makes sense considering that Villagers prefer to commute by golf cart rather than automobile. The Villages is also in the safest hurricane-prone area of Florida.

Villagers, on the other hand, are growing increasingly afraid of a strange threat: the ground suddenly opening up and swallowing them whole.

This March, a 10-year homeowner of the Village of Calumet Grove told me, “Everybody is scared,” pointing to a saucer-sized hole at his curb where sinkhole specialists excavated to check for weak spots. Seven sinkholes formed across the street and into a golf course a month earlier, producing a zig-zag fracture over the exterior of one house and forcing the evacuation of four residences. One has been sentenced. A town hall meeting that week drew five times the normal number of Villagers. With a tired laugh, the elderly neighbor adds, “It’s not a good time to sell.”

The Villages, despite its generally peaceful reputation, is a hotspot of sinkholes. They’re more common in Florida than anywhere else, yet we’ve spotted them on Maryland highways and even in front of the White House this week. And The Villages sits right in the midst of Sinkhole Alley, a region of Central Florida counties with the highest risk of sinkholes.

Florida Sinkhole

Florida Sinkholes Map By City, County and Address

Sumter County Sinkholes

When it comes to sinkholes, the Villages should not be singled out. The Villages is located in Marion and Lake counties, which are ranked #4 and #10 on RiskMeter’s 2011 list of the most sinkhole-prone areas in Florida.

The first is Pasco, which is bordered to the south by Sumter. A 260-foot-wide sinkhole opened beneath a Pasco neighborhood this summer, devouring two houses and condemning seven more, making it the county’s biggest sinkhole in 30 years.

For RiskMeter, an online program that provides hazard assessments for insurers, the huge chasm equaled the legendary Winter Park sinkhole in Orange County, which was ranked #8.

Citrus County Sinkholes

Citrus County, located just west of Sumter, is ranked #6 in RiskMeter and the fourth “grayest” county in the United States, based on the percentage of inhabitants over 65. Pasco and Marion are also among the top ten counties in the US for both the number and concentration of senior citizens.

Ocala County Sinkholes

A sinkhole in a fast-food lot in Ocala, near The Villages, swallowed a car, forcing the elderly couple inside to climb out. A man standing on the grass in The Villages slid through a five-foot hole’s trapdoor. A elderly couple in Glenbrook discovered a sinkhole just outside their front door.

Another Villager called 911 to report a “prowler,” only to find a black emptiness instead. Half of a couple’s house in the adjacent city of Apopka fell, taking with it “almost 50 years of memories.”

On the same day he returned from a trip to The Villages to check a possible sinkhole, I chatted with geologist and sinkhole specialist David Wilshaw. The little dip was created by a leaky irrigation line, but the terrified homeowner informed Wilshaw she hadn’t slept all night because she was afraid the ground might swallow her.

Sinkhole injuries are uncommon, but “perception is crucial,” according to Wilshaw, “especially with the older population.” They’re also worried that they’ll lose their “greatest investment”—their home—”during their golden years,” when they’re at their most vulnerable.

Hillsborough County Tampa Sinkhole Map

Use + or – sign inside the map or use your mouse wheel to zoom in and zoom out. Hover over your mouse to display a popup window for extra details.

For a complete list of sinkholes in Florida, click here.

Real Sinkholes

“While the data may contain some real sinkholes,” the website adds, “the majority have not been confirmed by specialists and are collectively referred to as subsidence occurrences.”

Sinkholes are prevalent when the geology under the land surface contains limestone, carbonate rock, salt beds, or rocks that may be naturally dissolved by groundwater passing through them, according to the USGS.

According to the USGS, sinkholes cause the most damage in Florida, as well as other Southern states such as Texas, Alabama, Missouri, and Kentucky.

Risk of Sinkholes

According to the FDEP, much of Florida Sinkholes is underlain with limestone, no portion of the state is totally free of the risk of sinkholes, however, there are some areas that are particularly vulnerable.

Sinkholes are particularly frequent in Pasco, Hernando, and Hillsborough counties in Florida, which are collectively known as “Sinkhole Alley.”

Paul Ivory, a Pasco County resident, told WFLA that he went outdoors to trim the grass in his backyard over the weekend and saw a six- to seven-foot-wide crater. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. That’s a sinkhole, I didn’t know what it was. I’m wondering how that happened so quickly “‘I told the station,’ he said.

Officials from the county have yet to label it a sinkhole or establish what caused it.

Devastation Throughout Florida

In the days since Elsa caused devastation throughout Florida, similar instances have been recorded in other regions of the state.

Paul Ivory, a Pasco County resident, told WFLA that he went outdoors to trim the grass in his backyard over the weekend and saw a six- to seven-foot-wide crater. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. That’s a sinkhole, I didn’t know what it was. I’m wondering how that happened so quickly “‘I told the station,’ he said.

Officials from the county have yet to label it a sinkhole or establish what caused it.

In the days since Elsa caused devastation throughout Florida, similar instances have been recorded in other regions of the state.

Place Names: Hillsborough, Lutz, Carrollwood, Town ‘n’ Country, West Park, Tampa, Del Rio, Plant City, Dover, Seffner, Mango, Thonotosassa, Orient Park, Palm River, Brandon, Bloomingdale, Riverview, Gibsonton, Keysville, Boyette, Sun City Center, Wimauma,

ISO Topic Categories: boundaries, geoscientificInformation, inlandWaters

Keywords: Sinkholes of Hillsborough County, Florida , Sinkhole, Karst, Caves, Sinks, physical, political, ksinkhole, transportation, physical features, geological, county borders, roads, boundaries, geoscientificInformation, inlandWaters, 2008

Source: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, Sinkholes (Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, 2008)

Map Credit: Courtesy of the Florida Center for Instructional Technology

Wrapping up message

Sinkhole in Florida is a prevalent issue that requires your focus. Sinkhole Florida is manufactured by the dissolution of the bedrock in the water. And then it ultimately results in a sinkhole. The climatic changes form sinkholes, but they may also occur because of poor developmental strategies.

The occurrence of a sinkhole in Florida depends upon the geological properties of that place. If you live in such a place, you should be attentive in this regard and always keep an eye on the sign, as it can protect you from future threats.

Conclusion

Open sinkholes bind surface and groundwater, allowing toxins applied to the site to reach specific water sources directly. Sinkholes used to be a familiar spot for dumping waste, such as rusted metals and pesticide cans. These practices resulted in heavily contaminated wells until the issue was finally detected, and the procedure was primarily discontinued (Levin, 2019).

Reference

Source: Sinkholes of Hillsborough County, Florida , 2008 (usf.edu)

https://www.foundationprosfl.com/ ( sinkholes alley to sinkhole affecting building or land )

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/florida/sinkholes-fl/ ( famous sinkholes of Florida)

https://fcit.usf.edu/florida/maps/galleries/sinkholes/index.php ( Florida sinkhole maps)

Grape, L. (n.d.). Sinkhole – Solving Drainage and Erosion Problems. Retrieved from Fairfax County: https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/soil-water-conservation/drainage-problem-sinkhole

Levin, N. (2019). 11 Largest Sinkholes in the World. Retrieved from Largest.org: https://largest.org/nature/sinkholes/

Panos, A. (2020). What are the causes of sinkholes? Retrieved from ice: https://www.ice.org.uk/news-and-insight/latest-ice-news/what-are-the-causes-of-sinkholes

Research, B. (n.d.). What causes sinkholes and where do they occur in the UK? Retrieved from BGS Research: https://www.bgs.ac.uk/geology-projects/sinkholes-research/what-causes-sinkholes-where-uk/

Frequently Asked Questions

Which State In The U.S. Has Most Sinkholes?

The most damage from sinkholes tends to occur in Florida, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania.

How Many Sinkholes Are There In Florida Each Year?

Florida is familiar with sinkholes. More than 6,500 sinkhole insurance claims are reported each year in the Sunshine State, BBC reported in 2014.

What Parts Of Florida Are Prone To Sinkholes?

Sinkholes are particularly common in the Florida counties of Pasco, Hernando, and Hillsborough—known collectively as the state’s “Sinkhole Alley.” Paul Ivory, who lives in Pasco County, told WFLA that he went outside to cut the grass in his backyard at the weekend and came across a hole that was six or seven feet wide.

How Many Sinkholes Incident Reported In Florida?

Based on the Florida Department of Environmental Protection database there are about 27,000 reported sinkhole incidences and sinkhole-affected areas across the Florida.

What Part Of Florida Has No Sinkholes?

According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, only two sinkholes have been recorded in the county historically. Fewer sinkholes are located on the east coast of Florida. Reported sinkholes have opened up in the DeBary, Deltona, DeLand, and De Leon Springs areas, generally near U.S. 17-92.

What Are Florida Soil Types?

Common Soil Textures in Florida. The most common soil textures in Florida are fine sand, sand, loamy fine sand, loamy sand, fine sandy loam, sandy loam, sandy clay loam, and sandy clay. On occasion, the textures clay, clay loam, and loam are encountered.

What Is The Main Problem With Soil In Florida ?

Soil subsidence is a growing problem. In recent years, soils around the Everglades are so shallow that farmers are struggling to manage water and grow crops.

I Am Going To Buy A House In Florida, What Should I Do?

You want to buy a Florida home that is safe and a secure investment, yet many home buyers are concerned about the possibility of a sinkhole on their property. Follow these steps:

Check Florida Department of Environmental Protection for the latest Sinkhole incidents data

Check for Visible Surface Depressions around the House

Get a C.L.U.E.

Read carefully and Interpret Insurance Reports Correctly

If the house is already repaired from sinkhole, then, Check the Quality of Remediation

Conduct a Proper Records Search

What Is C.L.U.E. ?

A C.L.U.E. (Comprehensive Loss Underwriting Exchange) report provides a history of your property insurance claims for homes, rentals and vehicles. … “That includes the date of loss, loss type and amount paid, along with general information such as policy number, claim number and insurance company name.”

Why Is Florida The Sinkhole Capital?

Florida’s peninsula is made up of porous carbonate rocks such as limestone that store and help move groundwater. Dirt, sand and clay sit on top of the carbonate rock. … When the dirt, clay or sand gets too heavy for the limestone roof, it can collapse and form a sinkhole.

Is There A Safe Zone Of Florida With No Chance Of Sinkholes?

Technically, no. The entire state of Florida is underlain with carbonate rocks, therefore, sinkholes could theoretically appear anywhere.

The only way to ensure that you don’t purchase property that might be prone to sinkhole activity is to not buy property in a Karst region.